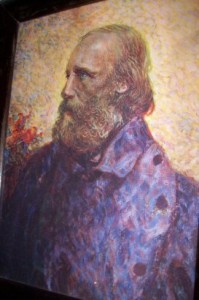

Garibaldi’s Blue Jeans

July 10th , 2012 Tagged with: Garibaldi

How many teenagers who wear blue jeans every day know that they are continuing a fashion that began about 140 years ago with the rugged hero of the Risorgimento movement?

How many teenagers who wear blue jeans every day know that they are continuing a fashion that began about 140 years ago with the rugged hero of the Risorgimento movement?

A Times correspondent wrote from the south of Italy on September 13 1860 when Garibaldi was busy uniting the country, “I had my first interview with the disinterested a brave liberator of Italy in his red shirt, a dirty pair of jean trousers

and worn out boots. Combing his long, thin hair at the glass stood the greatest patriot since Washington”.

It must be remembered that this patriot was originally a Ligurian sea captain who dressed, as his colleagues did, in trousers mad of that indestructible blue cloth named “blu de Gene”, blue of Genoa, from whence the appellation, blue jeans.

However blue jeans as a fashion phenomenon was to lie dormant for another hundred years, and surely the leader of the Mille would turn over in his grave to see young girls and grown women, instead of port workers, miners and sailors, wearing them.

Garibaldi was also the unwitting sponsor for other merchandise, especially in England where the ladies sported blouses modelled on the Red Shirts, called “Garibaldis”.

There were Garibaldi tie pins for the men and ads in t The Illustrated London News offered Dumas’ “Memories of Garibaldi” as the perfect book to read on the beach or train”.

The English love for souvenirs coupled with their adulation of the handsome, daring General, especially after his surprise invasion of Sicily in May, 1860, spawned an avalanche of commemorative objects, some of doubtful taste.

Besides the well-known Staffordshire figures of Garibaldi on horseback, there were Garibaldi silk scarves and bookmarks with portraits, and perfumes named after the hero were described as “irresistible”. There were sweets known as “Garibaldi balls” and raisin-studded “Garibaldi” biscuits which are still enjoyed throughout Europe today.

Garibaldi rose to such a height of popularity in England that the satirical magazine Punch always treated him with respect and near reverence, not the fate of other Risorgimento figures such as Pius IX, who was shown as a dribbling old man with a crooked tiara, or Napoleon III with patches and broken shoes, or King Ferdinando II of Naples who was pictured in Inferno in one cartoon soon after his death.

This hero-worship sometimes turned to persecution of Garibaldi by his English fans, as this extract from a contemporary English diary narrates: “Some ladies who sought an interview with him later at the Hotel d’Angleterre, asked him for a kiss a-piece, and that each might cut off a lock of his hair. Gen. Turr looked somewhat out of patience standing guard over Garibaldi with a comb and raking down the curls”.

The craze for Garibaldi produced many poems in honor of the brave General. Authors included Elizabeth Barrett Browning who penned her Poems before Congress in the quiet of her Florentine Casa Guidi, where she was visited by British envoys who considered her a reference point on the Italian situation.

Alfred Lord Tennyson showed his respect and friendship for Garibaldi in Memoirs, remembering the General’s visit with him on the Isle of Wight where they planted a pine tree together.

A striking contrast to the English hero-worship of Garibaldi can be found in the poetry and ballads published in the Irish press of the time. In one lively street ballad the Italian general is admonished, implying that his troubles – Anita’s death, his wound at Aspromonte and his exile on Caprera- were brought on as punishment for his having fought against the Pope.